Paula Talks Hamilton County’s History as Part of the Underground Railroad

Michael Kobrowski, the Westfield Washington Historical Society’s archivist and collection manager, recently mentioned to me that September is International Underground Railroad Month.

This is something relatively new. Maryland was the first state to officially proclaim the observance in 2019, but other states and Canada soon followed, including Indiana in 2021.

September was chosen for the observance because it’s the month two of the most famous people connected to the Underground Railroad, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, escaped from slavery.

The objective is to focus attention on the history of the Underground Railroad movement, especially in states that played an active role in it.

If you’re familiar with Hamilton County history, you’re probably aware Westfield was a major stop on the Underground Railroad, but there were also participants in the Bakers Corner/Deming area.

In “The Underground Railroad in Indiana,” an article published in the Indiana Magazine of History in 1910, author and Deming native Julia S. Conklin provides the names of several county residents who sheltered runaways and/or acted as “conductors,” guiding them from one place to another.

She ends her lists with “ . . . and many others.”

We may never know anything about those “many others” due to the secrecy that necessarily surrounded the operation. However, the article does include several stories about some of the locals who are known to have been active participants.

According to Conklin, the first people to engage in the Underground Railroad in the Westfield area were Louis and Judah Roberts.

As young men, the Ohio-born Robertses worked along the Ohio River for a cousin who introduced them to the Underground Railroad.

The Robertses moved to the Westfield area in 1834. Soon after that, they took in their first fugitive slaves, a group that had been sent north from their old Ohio River stomping grounds.

Another person who hid escapees was one of Westfield’s founders, Asa Bales. (I’ve seen multiple spellings for his last name, but the city of Westfield seems to have settled on “Bales.”)

Bales’ large barn concealed a secret cellar that sheltered many fugitives until it was safe for them to move further along the road north. A trap door disguised with hay or straw allowed Bales’ “guests” to receive food, drink or whatever else they needed during their stay.

One harrowing tale involves Luvica White, a widow who ran a Westfield tavern. (Conklin uses “Luvica,” but the widow’s headstone reads “Lovisa” and in a record from Henry County’s Duck Creek Monthly Meeting she’s “Louisa.”)

One night around 1850, the widow took in a female fugitive, whom she stashed in a room upstairs in her tavern. Shortly afterward, two men arrived seeking lodging.

White quickly realized the men were actually slave hunters and knew she had to move the woman to a safer place. The problem was, the only way out of the tavern was to go through the room in which the men were sitting.

Thinking fast, the widow dressed the woman in her own clothing, placed a bonnet and veil on her head, and walked her right past the men without skipping a beat.

Mrs. White took the woman to her son, Micajah, who lived nearby. The woman stayed at his home until it was safe to travel.

I especially wanted to mention Mrs. White’s story because her husband’s sister was Catharine White Coffin, the wife of Levi Coffin, the abolitionist sometimes called the “President of the Underground Railroad.”

The Coffin house in Fountain City is now a State Historic Site and is open to the public. (I’ve been there and it’s worth a visit.)

Some special programs have been scheduled at the Coffin home in honor of International Underground Railroad Month and this weekend Fountain City will be celebrating the Levi Coffin Days festival.

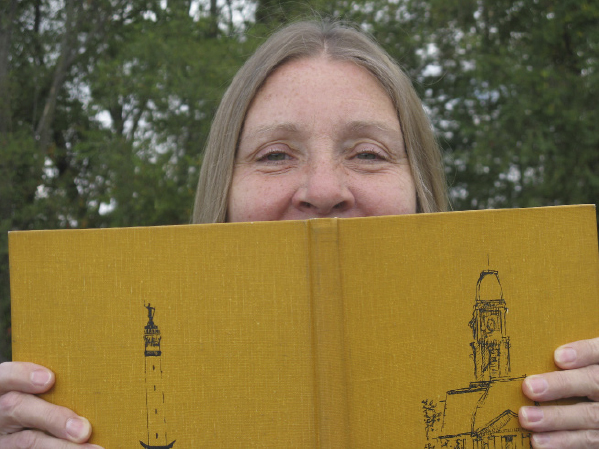

Paula Dunn’s From Time to Thyme column appears on Wednesdays in The Times. Contact her at younggardenerfriend@gmail.com