Roberts Discusses Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

I’ve been asked to re-run my columns about Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, more commonly known as GERD. That long name describes acid from the stomach (gastro) is found in the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach (esophagus) and goes in a backward direction (reflux).

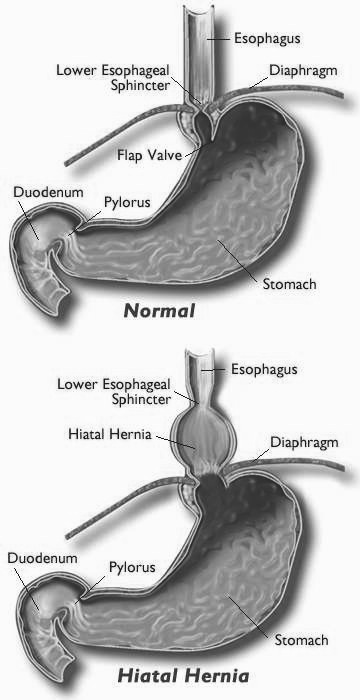

Once again, it’s helpful to know the anatomy when trying to understand a medical condition (see top diagram). The esophagus is a muscular tube that contracts in a rhythmic fashion to move food from just below the back of the mouth to the stomach. The esophagus passes through the diaphragm, the muscular dome that separates the chest and abdomen. The diaphragm helps form the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) that acts as a valve to keep acid in the stomach. Food passes through the LES into the stomach where it is mixed with acid to start breaking the food down for digestion.

It is estimated that between 14 and 20 percent of adults in the U.S. are afflicted with GERD. These estimates are based on surveys of patients who report heartburn, the primary symptom of GERD. The medical definition of GERD is “a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms (i.e., at least two heartburn episodes per week) and/or complications.”

The incidence of GERD is increasing in the United States. The reasons are not completely clear, but it is presumed to be due the rising number of overweight and obese individuals. However, normal weight individuals can suffer from GERD.

A diagram of the human stomach, showing both a normal stomach and one with a hiatal hernia, one of the causes of GERD.

A Hiatal hernia (bottom diagram) can lead to GERD. This condition occurs when the top part of the stomach “herniates” or pushes up through the hole in the diaphragm. When this occurs, the lower esophageal sphincter moves up away from the diaphragm, relaxes, and is not as effective at keeping food and acid in the stomach.

Additional risk factors for GERD include low muscular tone of the LES, loss of normal muscular function of the esophagus, excess production of stomach acid, delayed emptying of the stomach, and overeating. Alcohol can reduce the effectiveness of the LES. Fatty or fried foods, coffee, tea, caffeinated drinks, chocolate, and mint are all foods that can cause or worsen GERD. Smoking cigarettes is also a risk factor and also reduces production of protective mucus in the stomach.

Common symptoms of GERD include heartburn, regurgitation of food, difficulty swallowing and chest pain. Less common symptoms include pain with swallowing, water brash (excessive salivation prompted by acid reflux), sour brash (acid taste in the mouth, particularly when lying down), pain in the upper abdomen, and nausea.

Most people think of GERD as something that just causes heartburn, but it can result in more serious complications. These can be divided into those that involve the esophagus and those that don’t. While most of these produce only symptoms, some can actually cause injury or even lead to cancer.

The lining of the stomach is protected from stomach acid by a thin layer of mucus. The lining of the esophagus, on the other hand, is not designed to withstand constant exposure to stomach acid. When the esophagus is bathed in gastric juices, it can become inflamed and even ulcerated. This condition is called esophagitis and can vary from mild to severe.

Reflux with esophagitis can cause scarring of the wall of the esophagus. This can result in the formation of narrowed areas called strictures. Strictures may result in difficulty swallowing solids and food may feel like it’s getting stuck in the middle of the chest. If the strictures are severe the person may even have trouble swallowing liquids.

If cells that line the esophagus are exposed to stomach acid on a frequent basis, they may undergo structural changes to try to protect themselves. Excess acid exposure can also result in a condition called Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s can lead to cancer of the esophagus. The incidence of cancer of the esophagus has increased by a factor of two to six over the last 20 years.

There are also complications of GERD that occur outside the esophagus. If the stomach acid gets high enough in the esophagus, it can spill over into the larynx (voice box) and trachea (windpipe). This can cause a dry cough and also inflammation of the larynx (laryngitis) resulting in hoarseness and an irritating need to clear the throat. It can also trigger, and make asthma more difficult to treat. Acid reflux into the mouth, particularly during sleep, can also cause tooth decay.

Now that you’re an expert in what GERD is you’re probably asking how to avoid getting it and how to diagnose complications and treat it. Tune in next week for the exciting conclusion!

Dr. John Roberts is a retired member of the Franciscan Physician Network specializing in Family Medicine.