The Mysterious Mr. Morse

I doubt if many people today have ever heard of Joseph Morse, but at one time he was one of Noblesville’s more prominent residents.

In fact, he was so well regarded, his obituary in the June 1, 1877 Noblesville Ledger runs longer than a half page. Back then most people didn’t rate more than a paragraph, if that.

Born in West Woodstock, Connecticut in 1812, Morse was said to be related to Samuel F. B. Morse, the famous painter, and inventor of the telegraph and Morse Code.

I was skeptical of that claim at first, but it checked out. Morse’s father, Charles, was a first cousin to Samuel Morse.

In the late 1830s or very early 1840s, something caused a major rift between Morse and his family. Exactly what happened was a secret Morse took to his grave, but whatever the dispute was, it was serious enough to prompt him to cut all ties with his family and move west.

Eventually, he ended up in northern Kentucky where he made a living trading honey, ginseng, furs and other items found on the frontier.

His obituary notes that he often entertained his Hamilton County friends with “word pictures” of life along the Big Sandy River. (“His recollections of the early days and prominent men of Kentucky were vivid, and he took great delight in referring to them.”)

The one aspect of Kentucky Morse didn’t enjoy was slavery. He hated it and, being the kind of person who held strong opinions which he never hesitated to express, he made no friends among the local slave owners. Ultimately, his hatred of slavery prompted him to leave the state.

He arrived in Noblesville sometime around the end of the Civil War and established a jewelry shop in an area of George Vestal’s drugstore on the south side of the courthouse square.

In addition to selling jewelry, Morse sold and repaired clocks and watches. Later, he added plated ware, musical instruments, looking glasses, stationary, and window curtains and fixtures to his stock. He even sold wallpaper!

His main claim to fame, however, is that he was the driving force behind a revival of public interest in Llewellyn Spring, the mineral spring located on the bank of White River, a little south of Conner Street.

In 1874 or ’75, during a period of poor health, Morse somehow learned of the reputation for healing the spring had had among Native Americans. He tried drinking the water himself and within a few months he was fit as a fiddle.

He was so sold on the spring’s curative powers, he even had the water analyzed. (You can find the analysis in Helm’s county history.)

Thanks to Morse’s enthusiastic endorsement, Llewellyn Spring attracted people from all over for several years before interest died down and the spring again faded from history.

Morse’s good health didn’t last, either. He died in 1877, just two years after being rejuvenated by the spring.

Before the end came, Morse asked his friend, George Vestal, to notify his family back east of his death.

One of Morse’s two brothers and his sister were already dead themselves, but his sister’s widower was tracked down in Rhode Island and he showed up to look after the family’s inheritance. (Morse never married and being a workaholic, he’d amassed a tidy estate.)

Morse is buried near the main entrance of Noblesville’s Crownland Cemetery. Although his monument was undoubtedly impressive when it was erected, it now looks a little sad. It tilts like the Leaning Tower of Pisa and only Morse’s birth and death dates are still legible. The rest of the inscription has faded.

Those dates will probably be unreadable themselves before long, leaving behind yet another mystery associated with Joseph Morse.

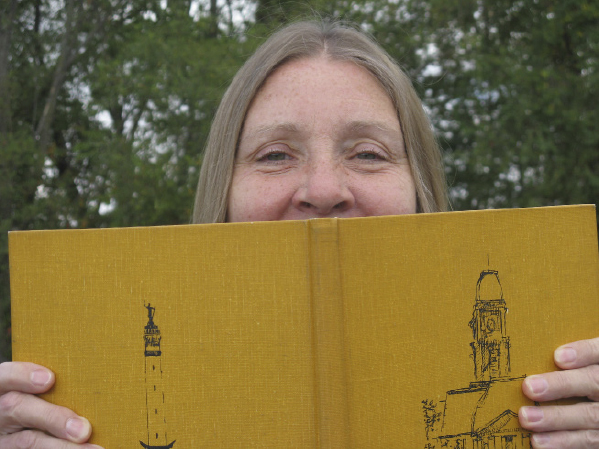

Paula Dunn’s From Time to Thyme column appears on Wednesdays in The Times. Contact her at younggardenerfriend@gmail.com