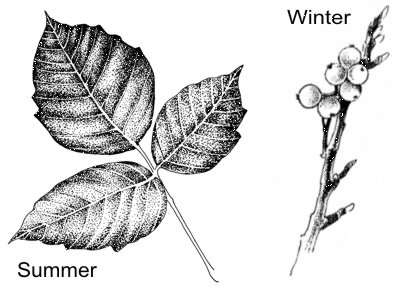

Leaflets Three…Let It Be!

Different seasonal variaties of poison ivy

Summer is almost here and a lot of folks are finally getting out in the yard to play with their plants. This will probably result in a lot of rashes showing up in doctors’ offices. Most of the rashes we see in the summer are caused by poison ivy, one of three plants in the genus Toxicodendron that are found in Indiana. This genus also includes poison sumac, and poison oak.

The physical appearance of the poison ivy plant is highly variable, though it always has leaves in sets of three (see illustration). A memory aid from my days in Boy Scouts lets me recall what it looks like – “leaflets three let it be, berries white a poisonous sight.” The plant sometimes has white berries in wintertime. Younger Poison Ivy plants are small and low to the ground. As they grow, they can be found in various sizes all the way up to thick vines attached by small tendrils to trees or other structures.

The rash of poison ivy, like most contact rashes, is caused by the reaction of the immune system to the plant’s oil on the skin. When dealing with poison ivy, sumac or oak, it causes a typical rash, known as “rhus dermatitis.”

In the case of poison ivy, oak and sumac, the offending chemical is the plant resin or oil urushiol. Urushiol is also found in mangos and the shells of cashew nuts. This oil can remain in the environment for years after a plant dies.

To develop rhus dermatitis, you must be sensitized to urushiol. This means you have to have had a prior exposure to the resin to activate your immune system. The typical rash then develops on subsequent exposures. Between 15 to 30 percent of people require numerous repeated exposures to urushiol before they have any reaction at all. It’s interesting to note that Native Americans, who have lived around these plants for centuries, react the least of any race.

The initial rash usually occurs 24 to 48 hours after exposure to urushiol. It appears as redness with blisters, usually found in a line where the plant brushed the skin. Areas of skin covered with clothing are generally spared unless the victim transfers the oil from clothing to skin that was covered (important health tip to males – if you’ve been clearing brush, always wash your hands with soap and water before using the bathroom).

People often have the misconception that fluid from the blisters can spread the rash. However, once the oil is washed off the skin with soap and water, the rash can no longer spread. Patients often wonder if it’s not contagious, why does the rash seem to spread? This depends on the amount of oil the skin is exposed to. If an area is exposed to a large amount of oil, it will break out sooner after contact. Areas that get a smaller dose may not break out for up to two weeks after the exposure. Someone might also be getting repeated exposures from clothing they were wearing or from pets that might have the oil on their fur. The entire course of the rash may last up to a month or so if left untreated.

Treatment of rhus dermatitis is based on the severity of the rash. If you know you have touched poison ivy, wash the area of contact immediately with lots of soap and warm water. Minor rashes usually respond well to cool compresses and either topical or oral diphenhydramine (Benadryl®). Over the counter 1% hydrocortisone cream applied three to four times a day can also speed resolution, though you should not use it around the eyes or mouth, areas of the body that have thin skin, and very sparingly on children.

More severe cases may require a trip to the doctor. We usually prescribe a steroid cream, ointment, or sometimes steroid pills. Pills are usually prescribed if the rash is found on the face or around the eyes. Occasionally scratching the rash may cause infection with skin bacteria. If this happens your health care provider may also prescribe antibiotics.

As always, an ounce of prevention beats a trip to the doctor. Know what the plant looks like. When you’re in an area with possible poison ivy, wear long sleeves, pants, and gloves. Avoid rubbing your skin with clothing or gloves that have come into contact with vegetation. Take a hot soapy shower or bath as soon as possible. Wash your clothing in hot water as well.

– Dr. John Roberts is a member of the Franciscan Physician Network specializing in Family Medicine.