The Origin of Cicero’s ‘Lead Mine’

While working on last week’s column, I ran across so many interesting stories about Cicero’s “lead mine” (see the last three paragraphs,) a follow-up column begged to be written.

The first people to discover lead ore in this area were Native Americans. (One source mentioned the Miamis specifically, but I couldn’t verify that.)

Until I did a little research, I didn’t realize how important lead was to Native Americans. They used it for ornaments, jewelry, paints and cosmetics. It was also a valuable trade item, even before the arrival of the Europeans and their firearms.

Because the Indians prized lead so highly, they kept the location of their source a closely guarded secret. However, one of Cicero’s early settlers, a man named Bill Jones, became friendly enough with them to be taken into their confidence.

Jones also refused to divulge the lead’s location. He simply collected the ore himself as the need arose.

On one occasion, Jones was at a maple sugar camp with a group of men who had a yen for some fresh venison, but were short on bullets. Jones volunteered to fetch all the lead they needed IF they promised not to follow him.

The men agreed and Jones left. A short time later, he returned with a load of lead ore “which was quickly smelted and moulded into bullets.”

Jones also supplied his neighbors with lead. Despite the neighbors’ repeated attempts to track him to his source, the wily Jones always eluded them.

Jones wasn’t the only person who discovered lead in this area, though.

At another sugar camp, some people who’d placed a couple of rocks in their fire to hold up the wood they were burning were surprised to see the rocks melt under the fire’s intense heat.

Sometime in the late 1850s, a stranger arrived in Cicero and tried to convince the richest man in town, Harrison Pickerill, to enter into a partnership with him. The deal was, Pickerill would buy a parcel of land the stranger claimed contained a lead mine and the two men would split the profits.

Pickerill turned the man down.

After the proposal was rejected, someone followed the stranger “up into the hollows, west of the creek and west of the graveyard,” but lost the trail after that.

The stranger was last seen carrying something tied up in a handkerchief as he hopped on a train and left town.

Around 1890, a local man encountered an old lead miner in Missouri. Upon learning his new acquaintance was from Hamilton County, the miner asked if Cicero’s lead mine had ever been “worked.”

The miner then revealed he’d been to Cicero about 50 years earlier and claimed he knew of a rich vein of lead that existed somewhere near there. He said the mine’s mouth was concealed by a big log, and added that, if the mine was ever located, a pick and a shovel would be found nearby.

The old man spoke of intending to return to Cicero to work the mine, but he died the following winter and took the lead’s location with him.

In the last years of the 19th century, lead ore was discovered on farms near Cicero and Perkinsville, and it was rumored Indians had had a source near Fishersburg, but I found no evidence of mines being dug at any of these locations.

In fact, back in 1883, Cicero resident and former state representative James R. Carson wrote to the Republican-Ledger insisting that any lead in this area could only have come from small surface deposits.

He pointed out that Bill Jones had died poor in Illinois, a circumstance that wouldn’t have happened had there been enough lead ore here for a profitable mining operation.

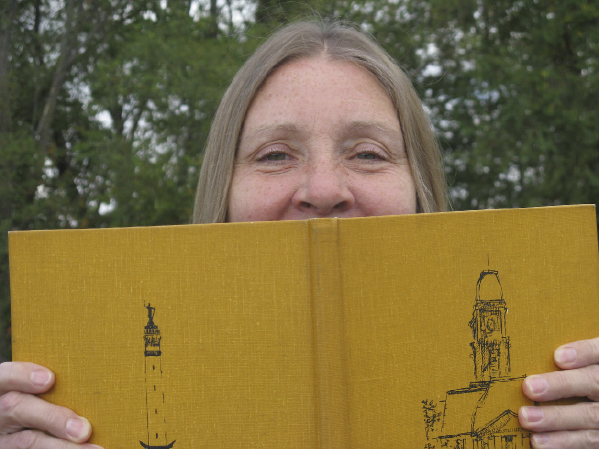

Paula Dunn’s From Time to Thyme column appears on Wednesdays in The Times. Contact her at younggardenerfriend@gmail.com