The Myth of Crownland’s ‘Glowing Tombstone’

Are you familiar with the myth of the glowing tombstone in Noblesville’s Crownland Cemetery? I was a senior in high school when a classmate told me about it.

My reaction ran along the lines of “Whuuut?” Although I’d lived here all my life, this was news to me.

My friend went on to embellish his story, saying it was rumored that the monument belonged to a scientist who’d died of radiation poisoning and that was why the stone glowed.

Yeah. Right. That’s when I knew for sure I was being fed a tall tale.

When I started doing serious research in the old newspapers, however, I discovered that, like many a tall tale, there was a tiny — VERY tiny — grain of truth to the story.

During the 1930s, Crownland actually did achieve a small degree of fame due to some strange lights that appeared in the cemetery.

But, before I get into those details, let me stop and describe the setting.

Back then, Crownland was outside the city limits, surrounded by farmland, most of which belonged to the County Farm. Monument Street east of 16th Street was little more than a country lane.

The closest homes — except for the house of the cemetery’s sexton — were about a quarter mile to the west in the Lincoln Park addition. (Lincoln Park is the area west of 16th Street, between Monument and North Streets — more or less.)

At that time, the cemetery was enclosed by a fence and each evening the gate (now the main entrance) was locked to keep out mischief-makers.

In other words, the graveyard was already a pretty spooky place when mysterious lights were first noticed there around 1930 or ‘31.

News of the discovery spread and soon people from all over the state began showing up after dark to see the lights.

In the beginning, the sexton, John Stern, found the whole business amusing. He knew there was a perfectly natural explanation for the phenomenon.

Stern told the Noblesville Daily Ledger in July of 1931 that what people were seeing was nothing more than light from street lights or the full moon, reflected off the polished surface of some of the tombstones.

Despite this published explanation, the cemetery continued to draw visitors, especially in autumn after the trees dropped their leaves and the lights were more easily seen.

One evening, Stern couldn’t resist having a little fun when a group of young people stopped outside the cemetery fence. As the youths discussed the eerie lights, the sexton let loose a few loud “whoops.”

He said later, “I never saw a crowd of young people run faster to their car than they did and the speed of that machine would have done credit to one of the Speedway racers.”

By 1935, Stern’s amusement had turned into annoyance. People were coming to the cemetery nearly every night. Some even climbed the fence and invaded the grounds.

Hoping to put an end to the nuisance, Stern enlisted the aid of Sheriff Alvin Baker. One night the two men waited near the “glowing” monument until midnight, intending to shoot a revolver into the air to scare off would-be trespassers.

It was a wasted effort. Although some cars stopped outside the gate, nobody tried to go past the fence.

The curiosity seekers kept on coming until the City Council cut off the light shining into the cemetery by putting shades — thin metal bands — on some of the street lights in Lincoln Park. Finally, people began to believe Stern’s explanation.

After that, the only lights seen in Crownland were lights that were obviously reflected from cars traveling east on Grant Street. Eventually, interest in the cemetery died down.

Note: I’m still looking for wooly worm sightings!

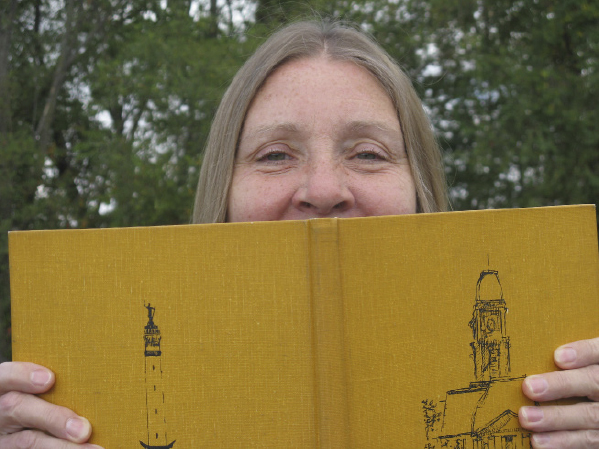

Paula Dunn’s From Time to Thyme column appears on Wednesdays in The Times. Contact her at [email protected]