A Life Well Lived: Conner Prairie’s Betty Gerrard, 101, Remembered

Betty Gerrard, who played the costumed interpreter role of Betsy Birdwhistle, Kate Bend, and the doctor’s Aunt Elizabeth, celebrates her 100th birthday in August 2021 at Forest Park Lodge in Noblesville. She passed away on Friday, Dec. 30, 2022, at age 101.

Noblesville’s Elizabeth Gerrard was known to her friends as “Betty.” But she will always be “Betsy Birdwhistle” to so many people who knew her from Conner Prairie.

Gerrard, who first came to Conner Prairie as a volunteer more than 55 years ago, played many roles during her years as a costumed interpreter there.

“I had all kinds of husbands,” Gerrard said. “Sometimes, I was a storekeeper’s wife. And the doctor’s Aunt Elizabeth who had a successful husband (and who played the piano by ear).” She was also the weaver’s wife.

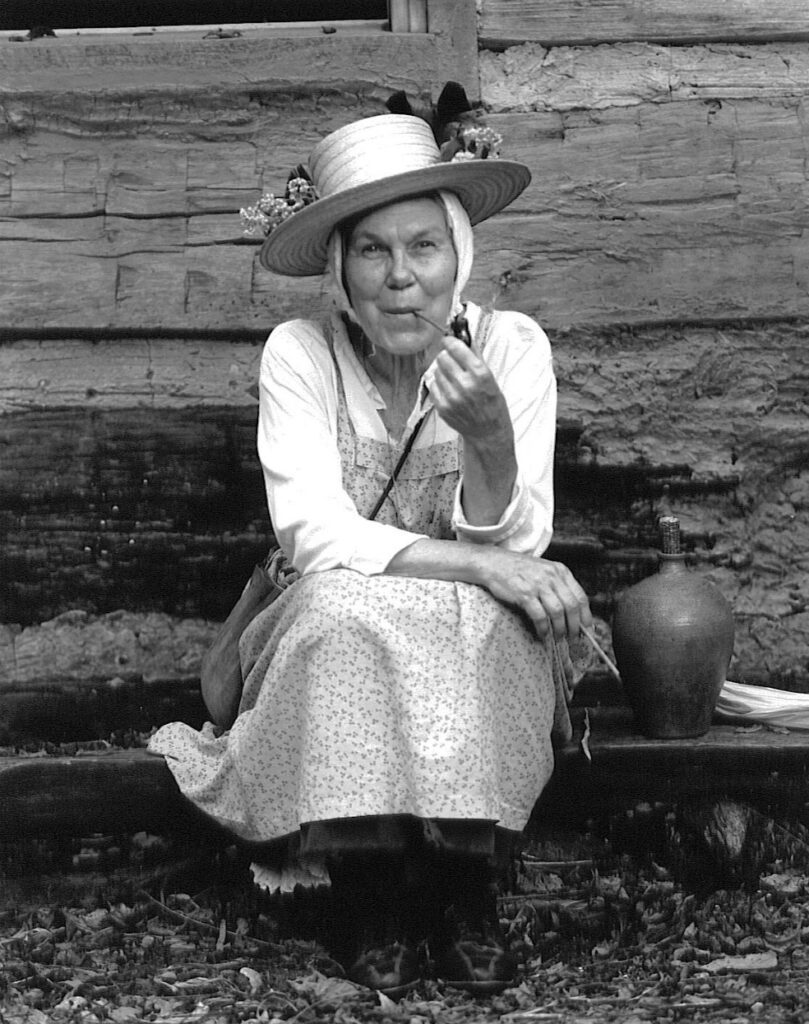

Her favorite character was Kate Bend, mother-in-law of the potter. “She couldn’t read or write or cipher. She had a pipe in her mouth and a jug on her hip. I neither smoked or drank but I played that character,” Gerrard said. “As Kate, I would go barefoot. How many jobs can you go barefoot?”

She made up Kate and Aunt Purity, along with her school teacher role, Betsy Birdwhistle. “I just loved the name ‘Birdwhistle.’ It was a name that was used in the 1830s, and it was fun for me.”

Gerrard said she was 46 years old, “a grown woman,” when she came to Conner Prairie to be a volunteer, which later turned into a paid position. “It was a wonderful job. We didn’t get paid much …. But the perks were wonderful. You met people from all over the world,” she said. Gerrard, who learned how to cook over an open fire, and how to roast potatoes in ashes, and all kinds of other hands-on skills, retired in 2008 after 42 years.

By now, many of my readers have already heard the sad news. The former volunteer and retired costumed interpreter passed away on Friday, Dec. 30, 2022. She was 101.

About 17 months ago, I was fortunate to be invited to Gerrard’s 100th birthday celebration. She turned 100 on Friday, Aug. 6, 2021.

The morning of her party, on Saturday, Aug. 7, 2021, I asked Gerrard about her key to longevity? “I feel like laughter and love has a lot to do with it,” she replied. “…I’m grateful for what I have,” said the centenarian who lived the past eight years in Sanders Glen assisted living facility in Westfield.

“I’m 100 and one day old today,” Gerrard said on that day after her birthday.

“I’m tired. Sanders Glen had a party for me yesterday. And then my family took me to Hollyhock Hill for chicken dinner.”

So what does it feel like to be 100? “I don’t feel any different. I don’t know what to expect,” she said.

The telephone conversation occurred just hours before a birthday celebration on Aug. 7, 2021, at Forest Park Lodge, where folks she’s known for more than half of her life came to celebrate her 100th.

Gerrard wore a sash that read “100 years loved” and smiled her sweet smile with every guest who stopped at her table for a snapshot, a kind word or to reminisce.

Photos of her life decorated a table, and a lifesize timeline display welcomed guests just inside the door.

Elizabeth Nancy Ann Alexander (named for both of her grandmothers) was born Aug. 6, 1921. She was grateful for good parents, her dad living into his 70s and her mom into her 80s. Her mother fried chicken for 16 years at Hollyhock Hill, where her mom, dad, brother and herself also worked there at one time.

Betty Gerrard, whose favorite character was Kate Bend, mother-in-law of the potter,” said, “She couldn’t read or write or cipher. She had a pipe in her mouth and a jug on her hip. I neither smoked or drank but I played that character,” Gerrard said. “As Kate, I would go barefoot. How many jobs can you go barefoot? Gerrard passed away on Friday, Dec. 30, 2022, at age 101.

She graduated from Broad Ripple High School in 1939 and took her first job at L.S. Ayres as a “stock girl.” During WWII, she also worked at Lucas Harold, the Norden bombsight on Arlington Avenue in Indianapolis and lived at home with her parents.

She met her husband, 1941 Noblesville High School grad Jimmy Gene Gerrard, in Broad Ripple, at age 18, and married at age 20 on June 2, 1942, during a seven-day leave from the U.S. Army, for which he served 26 months during World War II beginning in 1941. (Her family had moved to Noblesville before marrying.) The timeline included living in Hattiesburg, Miss., in 1942, and in Texarkana, Texas, in 1943. They moved into a house that her in-laws bought in Noblesville on March 1, 1946, and she gave birth to her first child, son, Erick G. Gerrard, on March 1, 1947. Then, they lived in Chicago, Cleveland and Texas, before Jimmy took a job with Allison Transmission in 1951 and became supervisor of transmissions, staying for 31 years. Then a daughter, Melody Ann Gerrard was born April 9, 1954, in Columbus, Ga. Gerrard also has a grandson, granddaughter and a 4-year-old great-granddaughter. The family house where Gerrard and her family most recently lived on South 10th Street was demolished in summer 2022 just before the Dairy Queen was demolished, to make room for the future Pleasant Street roundabout.

Gerrard came to Conner Prairie in 1966. “I didn’t go to get a job,” Gerrard said. After her volunteer position changed to paid, she started earning $3 a day.

Gerrard had kept a diary since grade school, writing about life, boys, work, family and the war. She still had a journal, and lots of photos of her life.

“Betsy and I became musical best friends at Conner Prairie when I was 16 or 17,” said Sue Payne of Fishers, Conner Prairie’s first youth volunteer in 1965 and who has volunteered or worked at Conner Prairie for more than 55 years. (Payne is a member of the textiles staff and leads the museum’s youth spinning program in its 19th year.)

At the time, Dick McAllister, the director of interpretation, figured music would add a whole new dimension to Conner Prairie and bought handmade cherry dulcimers, Payne said. Two of them were courting dulcimers; two sets of strings so players could sit facing each other. “A courting couple could sit within earshot of the parents and they would listen for both sides to play,” Payne said.

“Betsy did a lot of research on the dulcimer and was phenomenally talented musically even though she had never had a single lesson,” Payne added.

“She got me started playing and, for years, Betsy and I played dulcimer together in the Shady Grove in Prairietown, down on the still house porch (which is long gone), we played on the front porch of the Conner House for groups (also long gone and traveled for various outreach programs as well playing for thousands of school tour children while they were waiting to head out on the grounds.”

Payne, who each August leads the spinning youth volunteers at the annual Sheep to Shawl spinning competition at the Indiana State Fair, said, “Betsy was also a spinner and that was a strong bond as well. We attended spinning workshops together.”

Gerrard was born three years after World War I ended and was ages 18-25 during World War II, 1939-45. Her dad was too old to go to the military, said Gerrard, who had three brothers; two who died in infancy, while one brother, 94, lives in Arizona.

Her dad would move if he could find a better trade. “So he picked up work where he could find it.” He worked as a farmhand at Indianapolis Gas and drove a milk wagon with a horse for Polk Milk Co.

“She would tell me stories of her life during WWII,” Payne said.

Betty loved dancing and would share stories of going to the local USO places and dancing with soldiers who were on leave.

“I feel like I’m very blessed. I had blessed parents who loved me,” Gerrard told me. “These were the depression years. We didn’t have any money, but we had what mattered.”

She got to Conner Prairie after meeting a woman who volunteered at the museum. “I thought, ‘Maybe I would like to do that.’ I went out and met the acting director.”

At the time, there were only volunteers. “That’s how I happened at Conner Prairie. I wasn’t sure I could do it because I realized that all those school children would be looking at me.” She didn’t think she could do it. But 42 years later, Gerrard retired from her volunteer position-turned-job that she turned into one of the most interesting positions at Conner Prairie.

That was 14 years ago that she retired and has since been enjoying life.

Gerrard, a couple of years ago, handwrote and mailed this journalist a thank-you note for a column that I wrote about Payne, Gerrard’s former co-worker. I saved the note, thinking that I would write a column on Gerrard some day, and I did write a column for her 100th birthday.

Little did I know at the time of receiving the correspondence that Gerrard was approaching 100.

And, “oh, yes,” she remembered me when I called her the day after her 100th birthday. Gerrard said, “Yes, I did write to you. You wrote about something, and I was so pleased that you had.”

Rest in peace 101-year-old Betsy Birdwhistle. We will forever remember you.

And as Payne once said to me about Gerrard: “No one has taken her place, no one could.”

Funeral services will be private. Read Gerrard’s obituary this week in The Times.

Contact Betsy Reason at betsy@thetimes24-7.com