Westfield Grad Recalls Coliseum Explosion 60 Years Ago Today

By: Betsy Reason

Kirk Kirkendall’s freshman yearbook photo, Westfield High School, 1963-64.

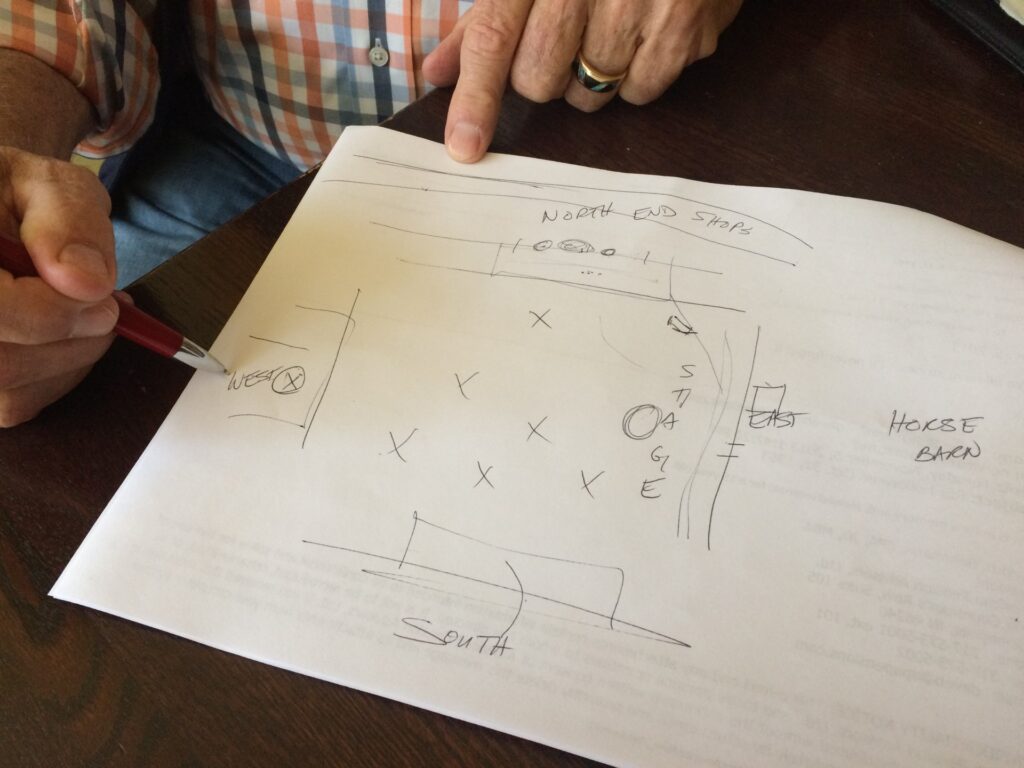

Kirk Kirkendall drew a quick floor plan on a piece of paper of where his family sat on the west end of the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum on the night of the deadly explosion that occurred Oct. 31, 1963. “Here is where the explosion took place,” he said, pointing to the north set of audience seats on his hand-drawn map

It was 60 years ago today. Halloween night Oct. 31, 1963.

Kirk Kirkendall was a freshman at Westfield High School and two days from turning 15.

He was attending the Holiday on Ice Show at the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum with his family.

It was on that night that a violent explosion shook the Coliseum, killing 74 people and injuring nearly 400.

“It’s something I’ll never, ever forget,” said Kirkendall, who was among about 4,000 people attending the ice-skating show, when just after 11 p.m., during the show’s finale, an explosion occurred when gas reportedly leaked from a faulty valve on a propane tank ignited.

It was one of the worst tragedies in Indiana history. Today is the 60th anniversary of the tragedy.

The evening started as a celebration for the Kirkendalls. He and his brother, Gary, were celebrating their birthdays. His birthday was Nov. 2 and Gary’s, Nov. 9, a year apart. “For me, it was a big year because I was turning 15, and I was going to get my driver’s license.” They were with their mom and dad, Flavia and Charley Kirkendall, their sister, Charlene, and Gary’s friend, Jeff Beals.

Kirkdendall, who’ll turn 75 on Thursday, said, “Things that I remember about that night were, we had an intermission and so we went out and we got an ice cream. Along the hallway on the outside walls, they had concessions, a cafeteria…. We just sat out there and talked about Christmas, and Thanksgiving. Of course, I was excited to take my driver’s test….”

Then they went back to their seats to watch the rest of the show. He drew a quick floor plan on a piece of paper of where his family sat on the west end of the Coliseum. “Here is where the explosion took place,” he said, pointing to the north set of audience seats on his hand-drawn map.

“Over in this area, they had a little cannon, and as the show was wrapping up, the skaters were skating off, and they discharged the cannon to signify it was the end of the show,” he recalled. “When that cannon went off, there was an explosion over here in this (north) side where the gas had accumulated in the stands. The next thing I know, I’m watching people over here to my right, screaming and running. And then there was a second explosion and flames came out. Then the bodies began hitting the ice.”

He was still sitting in his seat with his family, but he instinctively knew he had to help. Even though everyone else was trying to leave.

“For some reason, I jumped over the guardrail down to the ice. As I came upon the injured, some were breathing, some were not,” Kirkendall recalled. “Those that I could see breathing — some with their face in blood and water — I propped up their head with a coat, scarf, purse, anything to stabilize their position so they wouldn’t suffocate.”

“I came down to see what I could do to help,” he said. His dad followed, while his mom, brother and friend headed to get the car.

“Here we were. There’s this show that we came to watch. And all of sudden, there were bodies strewn all over the ice,” Kirkendall said. He was a Boy Scout but didn’t have extensive first-aid training. But he walked around, from body to body on the floor, turning their heads. “I figured someone would be coming to help soon,” he said.

Kirkendall wasn’t nervous or scared during the situation. “I knew these people needed help. I just wanted to do what I could.” He remembers how they went into the stands and tried to move steel and concrete debris from a mom and a little boy who were trapped under the rubble. He remembers how 4-by-8-foot sheets of flooring on the ice were used as stretchers to carry the injured to the ambulances and vehicles. He remembers how he gathered up purses and staged the valuables in a safe place.

“Would I like to have done more? Sure, everybody in that situation would like to do more. I felt that I did the most that I could do. And then to feel so helpless that there was no way that we could help those people, it was just a terrible feeling,” he said.

Growing up the oldest of three children, he always looked out for his siblings. “The 1960s, for me, were really life-changing years. My mother died of a massive fatal heart attack in 1966 (July 21), and my father was killed (instantly in an Acetylene torch accident) three weeks after I started at Butler (University) in (September) 1967,” said Kirkendall, a 1967 graduate of Westfield High School. “Had no idea I would lose both of my parents less than four years later.” (Sandy Meredith Rodenberg, whose 17th birthday was on the day that Kirkendall’s mother died, was Kirkendall’s steady girl in 1966 and who attended both of his parents’ funerals.)

From all of that, he said, “I learned how to survive.” While he couldn’t concentrate on school, in February 1968, he joined the U.S. Air Force and went to Vietnam, 1969-1970. Then he returned and earned a college degree in business from Indiana University and worked in transportation and distribution for 20 years, then the insurance business since 1987. (Sandy Meredith Rodenberg died just a week ago, on Oct. 24, 2023.)

Kirkendall said, “God’s been good to me. I did what I think anybody would do in my circumstances.”

He said his own children and grandchildren were taught to help others and to be competent and prepared and to work hard, to be the best they could possibly be, the very qualities he learned from his own parents.

Through the years, he has happened to meet others who had some involvement in the tragedy. In 1978, when he was distribution manager for Maplehurst Deli-Bake, he met a retired firefighter from Indianapolis Fire Department, who was off duty but headed to the Coliseum explosion in his station wagon and ferried a number of victims to local hospitals. Later, he became a member of the Noblesville Elks Lodge and struck up a conversation with a member named Finney, whose father was chief of surgery at St. Vincent Hospital and who was picked up by a fire engine that night to go to the hospital for the coliseum emergency.

“It has been interesting to see how ironic my ‘coliseum’ journey has taken me,” Kirkendall said earlier this month. Through the years, he has lived in Fishers, Noblesville, Sheridan and Westfield.

His sister, Charlene Fairman, just a few days ago said she could still remember that night, too. “For some reason, I thought it was a cowboy event on the ice and that when it first happened, it was part of the act,” said Fairman, who has only returned to the Coliseum twice in her life and wasn’t comfortable either time.

Sharing his memories with The Times originally eight years ago, Kirkendall hoped maybe somebody would read his story. “Maybe it will be the little boy who was trapped with his mother. Maybe it will be someone from the fire department who came in and saw these bodies on the ice; they weren’t face down and they were still breathing. Maybe they were saved.”

Over the past several weeks, he has told his story many times to a number of people.

He’s always wondered what happened to some of those people he tried to help. “The nagging thought is always: ‘Did anyone I help on the ice make it out or live? The most prominent thought is the boy and his mother, trapped in the twisted concrete and rebar. Did they survive? Always wondered and still do. What were their names?”

Kirkendall said he’ll be thinking about it all today, 60 years later. He said, “I still wonder.”

-Betsy Reason writes about people, places and things in Hamilton County. Contact The Times Editor Betsy Reason at betsy@thetimes24-7.com.